Heritage Trail Location 5

Photo 1 - The Spa Baths in Nov 2022

You are now looking at the Spa Baths where the history of Woodhall Spa began. It was here in 1821 that John Parkinson, a land agent for Sir Joseph Banks of Revesby, sank a shaft to find coal, but instead hit a spring of salt water. The shaft was abandoned in 1822 and the water overflowed into a stream where it cured sick cattle who drank it. People then started to drink the water as a cure and initially bathed in an open wooden tank.

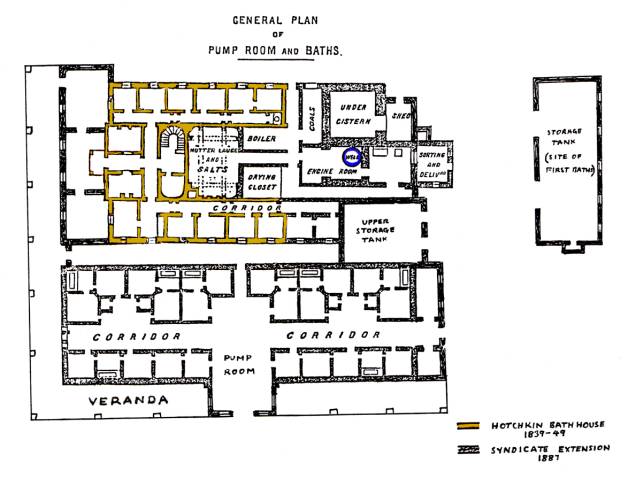

This encouraged the local landowner and squire Thomas Hotchkin, to build a brick bath and a windlass in about 1829/30. Its fame spread and in 1838 / 1839 he built a proper bath house with 6 treatment rooms and a hotel where all the latest treatments were available to the visitor. Hotchkin also laid out parkland with shrubbery and walks, all at a cost of (then) £30,000. This was continually expanded and in 1887 was bought by the "Syndicate", a group of businessmen who enlarged the Spa Baths and the Spa Hotel (later the Victoria Hotel), and laid out attractive wooded gardens and walks.

The timbered roof of the pump room and the present frontage was designed by C. F. Davis for the Syndicate. It is the main visible feature left after the collapse of the well in 1983, although the main part of the former Hotchkin bath house still exists around the back, but is obscured by the pebble dash frontage.

The timbered roof of the pump room and the present frontage was designed by C. F. Davis for the Syndicate. It is the main visible feature left after the collapse of the well in 1983, although the main part of the former Hotchkin bath house still exists around the back, but is obscured by the pebble dash frontage.

The Syndicate included:

The Right Honourable Edward Stanhope, M.P. for Horncastle,

The Right Honourable Henry Chaplin M.P.

Sir Richard Webster M.P.

T. Cheney Garfit Esq., Louth

The Reverend J. O. Stephens, Rector of Blankney (who was the secretary).

Sir Stafford Northcote, (Lord Iddesleigh)

Lord Alverstone, Lord Chief Justice.

They also commissioned Richard Adolphus Came, a London architect who later settled here, to design a "garden city" for Woodhall Spa. The names of the "Syndicate" are remembered in the road names to the South of the town which they hoped would be a large suburban style housing estate. It was never completed due to slowness of selling building plots and, consequently, the investors lost most of their money.

Why look for coal at Woodhall Spa?

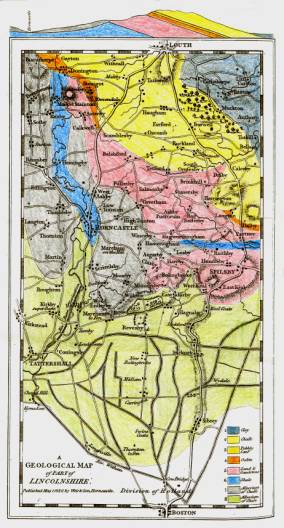

Map 1 - Woodhall Spa area

In the early 19th century, this area was a desolate piece of sandy and boggy wasteland. The area was largely uninhabited and, despite the enclosures of the 18th century, largely uncultivated, especially the area around the Tower of the Moor (a remnant of late medieval building to the east of the Spa Baths). Kirkstead was the largest village in the area with a population in 1811 of 110 with 26 houses: an odd place to sink a coal mine.

In the early 19th century Britain was advancing into the industrial revolution. Consequently, there was a tremendous demand for coal, not only for the new steam engines but also for domestic heating. In an isolated area like Lincolnshire, the cost of transport via canals, the main form of transport for bulk cargo, was high. Entrepreneurs looked enviously on the profits made by land owners sinking coal mines on the sides of the Pennines. They also saw that the further East, away from the Pennines the mines went, the deeper the mines had to go to obtain coal, until they were too deep to be exploited with the technology then available.

But surely, people argued, there must be coal close to the surface in Lincolnshire!

Map 2 -

Areas on the West side of the Wolds frequently turned up coal when they were ploughed. Coal was also being washed up on the beach. This was before steam ships and, although cargoes of coal from passing ships were often washed up on the beach, this was not enough to account for the coal found.

In 1816, a land surveyor, Mr. Edward Bogg, wrote a paper for the recently formed Geological Society. In it he described the geology and the rocks found in the Wolds area of Lincolnshire. He also included a map, a copy of which, with some modifications was published in 1820 by George Weir and is reproduced left.

The map shows rocks dipped to the East, and we now know that they continue to extend under the North Sea. The map also shows a large area on the West side of the Wolds covered by "alluvium of shale" (green) and "alluvium of chalk" (grey). They were called "alluvium" because they were laid on top of the eastward dipping rocks and it was thought that they were laid down during the Biblical flood. It was these "alluviums" that contained fragments of coal oil shale, thought to be washed out of the rocks just below the surface.

Similar oil shale and fragments of coalified timber were found at Donnington on Bain in a bore hole sunk by Edward and Thomas Bogg. They went down 100 yards (92 metres) without success but found enough evidence to convince them that the deeper they went, the better the results would be.

Edward Bogg published their results and suggested that seams should extend under the Wolds and out to sea where the sea was washing the coal out of the rocks.

In the early 19th Century the coal seams were thought to extend under the Lincolnshire Wolds and be eroded under the sea to produce coal fragments found on the beach. ‘Jetty coal’ is a old word for woody coal.

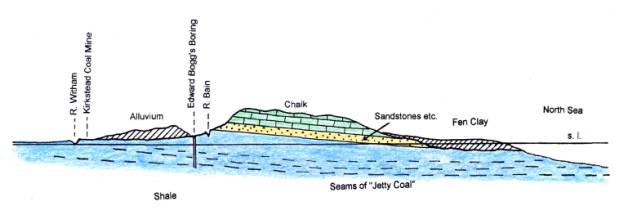

Figure 1 - Geological cross section of Lincolnshire

Armed with this, and similar information, coal prospectors realised that the further West they went from the Wolds, the closer the coal would be to the surface. Since the land to the West of the River Witham was covered with limestone and sandstones; just East of the River Witham would be a good place. South of Horncastle, and in ditches near Stixwould patches of the same clays investigated by Bogg were found. A well drained site, slightly higher than the then marshy areas around like the Woodhall Spa area which sits on patches of sandy gravel on top of the clays, would be an ideal place,.

Digging for Coal

Possibly two shafts had been sunk in the area when it was reported that some coal had been found as early as 1813.

Several speculators were involved before a more serious attempt was made about quarter of a mile east of Kirkstead Bridge by a Samuel Stainforth in 1819. After reaching a depth of about 190 metres the attempt was abandoned because only thin seams of coalified material had been found.

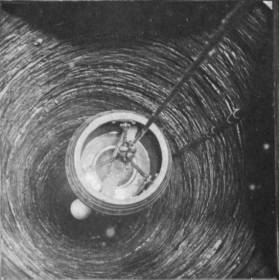

Photo 3 - A view down the Spa Baths well showing the barrel used to lift the spa water. The sides of the well show brickwork and paler rings which are the rings of oak blocks to which the original ladders and staging was fixed. Photographed by J. Wield c.1890. (Photo courtesy: Woodhall Spa Cottage Museum).

Eventually a land agent for the Banks estate, John Parkinson, became involved in the attempt. John Parkinson had three aims; to build a city, to plant a forest, and to sink a coal mine. The first was the development of New Bolingbroke, the second later became the Ostler's Plantation on Kirkby Moor, and the third was the Woodhall coal mine, started in 1821, on land owned by Thomas Hotchkin, the Lord of the Manor of Woodhall. All three proved to be financial disasters. The miners were encouraged to keep going by finds of small amounts of coal and carbonised wood, and the hope, in the light of the then geological thinking that better coal would be found deeper down.

A 3 metre diameter shaft was dug down to a depth of 256 metres, using a system of stage and ladder construction. Strata containing the weaker shale was bricked up with dry brickwork and every couple of metres or so a ring of oak blocks was fitted in to which could be fixed ladders and staging.

It was probable that mine waste was lifted up by a horse gin since this was only a trial shaft and bringing in a steam engine and the coal to fuel it would have been costly. The railways did not come into the area until 1844. Eventually, after boring a further 110 metres, at a total depth of 368 metres (1200ft), the attempt was abandoned in 1823 and the mine covered over. In 1826 Parkinson went bankrupt.

So what went wrong?

There are no thick seams of coal in the Upper Jurassic Shale, where the miners thought that they would find coal. There are oil shales in the top part near the Wolds, and these will burn, but poorly. We now know that the "alluvium" was in fact laid down by glaciers about 400,000 years ago, and these glaciers came from the North bringing coal scraped off the Pennines and North Yorkshire. Similar glacial deposits containing coal, also occur off the East side of the Wolds, but are of a different date, and it is from these deposits that the sea washes out the coal.

When John Parkinson didn't find the coal he was convinced was there, he went deeper and deeper. No records were made at the time and he probably didn't realise that he had gone through the shales that he was trying to find coal in, especially as he found similar shale beneath the Middle Jurassic from which the Spa water comes. The rocks that Parkinson stopped boring in come to the surface West of Lincoln, near the Trent.

Today we know that there are thick coal seams under Woodhall Spa, but at over 1500 meters deep they are much too deep for even today’s technology. However, they have generated gas where they pass out under the North Sea.

The Rise of the Spa

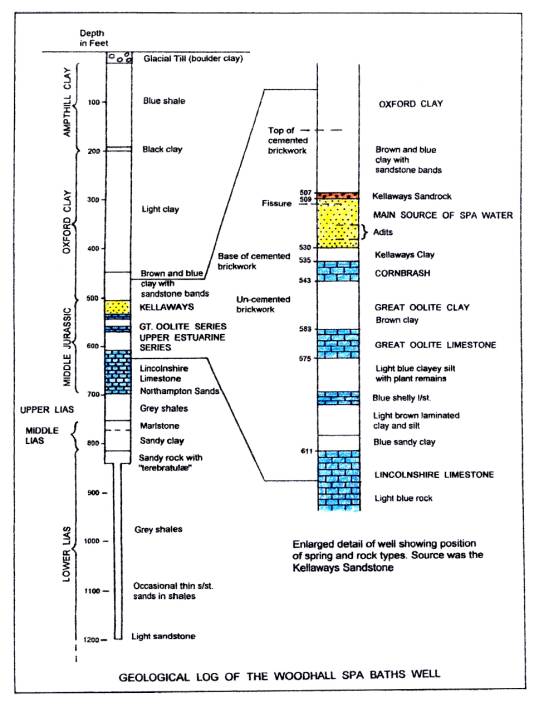

Figure 2 - Section of the Spa Baths well showing the strata the miners passed through and the source of the Woodhall Spa water. It is now thought that some of the water came from the other strata the well passed through. Czajkowski M.J., ‘The Source of the Woodhall Spa Mineral water’, Mercian Geol., vol. 15 part 2, (2001).

During the sinking of the 3 metre diameter shaft, the miners had cut across a spring at a depth of 159 metres (520 feet), which had to be bricked up to prevent the shaft flooding.

Eventually this water seeped into the shaft and filled it up. The water, so the story goes, overflowed into the stream by the side where it was drunk by some sick cattle owned by Thomas Hotchkin. The cattle were cured and the water, as early as 1824, began to get a reputation as a health cure.

This encouraged the local Squire, Thomas Hotchkin, to build a small bath house, containing eight bathing rooms, in 1839. The Spa's reputation spread and following the advice of Dr. Granville, a well known authority on Spas, the bathing rooms were improved and the water analysed. The water was found to be unusual because is contained very high levels of iodine and bromine, thought to be beneficial in curing all ailments in 19th Century Britain.

By 1849 a complex involving a high class bath house and a hotel, the Woodhall Spa Iodine Hotel, later called the Victoria Hotel, had been constructed. In the 1880's and 90's the complex was again modernised and enlarged by the Syndicate.

By 1849 a complex involving a high class bath house and a hotel, the Woodhall Spa Iodine Hotel, later called the Victoria Hotel, had been constructed. In the 1880's and 90's the complex was again modernised and enlarged by the Syndicate.

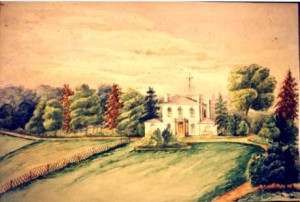

Figure 5 - Watercolour painted by Miss Hotchkin in about 1865. The two low side buildings contained the treatment rooms. Image courtesy: Woodhall Spa Cottage Museum.

Woodhall Spas heyday was from perhaps 1890 to the First World War. During this time adits (horizontal tunnels) were sunk into the Kellaways sandstone, the source of the water, to obtain more water though supply was always difficult when demand was high, resulting in closure of Spa Baths during the winter months.

The water was originally drawn off by a hydraulic belt, a continuous felt belt, like a roller towel, which was dipped in the well and then squeezed though rollers to remove the water. Later a steam engine, made by Roby of Lincoln, was installed in the 1880s. The steam engine was removed in the early 1960's, when an electric pump was fitted, and is now in the Museum of Lincolnshire Life, along with the barrel in which the water was lifted.

Figure 6 - General plan of the Spa baths after extensions by the ‘Syndicate’ in 1887. The original Hotchkin building (yellow) was enclosed by the later buildings now fronted with pebbledash and have remained largely intact. Adapted from various sources including a prospectus published by the ‘Syndicate’ in 1887

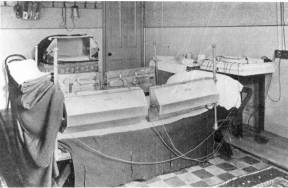

Whilst in the mid 19th Century treatments were related to the benefits of drinking the water, or bathing in it, to relieve gout, there was a change towards rheumatic treatments in the 20th century. The water being used in pools because of the extra buoyancy it gave when patients' joints were exercised.

Numerous other treatments were offered. These included treatments fibrositis, nervous disorders, heat disease, intestine ailments and various skin treatments.

Treatment methods also included the use of “Fango”, the salt impregnated mud extracted from the source rock when the adits were cleaned or enlarged (this was done on a regular basis), heated and applied as a poultice. “Motherlye”, a concentration of spa water and hot wax treatment was also used. By the 1920s interests in radiotherapy meant that ultraviolet ray and electrical heat treatment was being offered.

Photo 4 - Steam engine built by Roby of Lincoln and installed in 1880. The barrel contained non returnable valves which allowed the water to be hoisted up. A tray was swung under the barrel, the valves opened and the water drained by chutes under the floor to storage tanks. (Photo courtesy - Woodhall Spa Cottage Museum).

During and after the First World War the Spa went into a decline; the Spa Baths closed for a time and was eventually bought by the Weigalls, who owned Petwood House, now a hotel. In the 1930s they set up the Spa Baths Trust to keep the Baths going before they left the area. Petwood House became a Hotel. The Spa Baths continued to supply treatment for rheumatism using the spa water. Water was still drunk locally, though not to the same extent as in the 19th Century.

Various treatment rooms described in brochures issued by the Spa Baths in the early 1920s are shown below

Photo 11 - The Spa well collapsed, on the morning of the 23rd September. The upper brickwork has collapsed and is being enlarged by the swirling water. Parts of the surrounding buildings are beginning to collapse into the hole. (Photo courtesy - Woodhall Spa Cottage Museum).

Post Second World War

With the setting up of the National Health Service in 1946, the Spa Baths supplied spa water for rheumatic treatment. A larger pool was built within an old storage tank in a building at the back and equipment was installed to assist patients to enter and leave the pool.

The patients were brought by ambulance or stayed at the Alexander Hospital which was originally built on the instigation of Rev. Otter J. Stephens of Blankney, one of the "Syndicate" in 1890. This hospital is the large building just past and opposite the Golf Hotel, built in the Queen Anne Revival Style. It continued to be used by the National Health for patients attending the Spa Baths until 1983. It is now a block of flats.

Most of the treatments used in the 20th century relied on application of heat, either through the hot water douches and massages in the various treatment rooms illustrated above, or immersion in the swimming pool.

Photo 12 - Buildings continued to collapse as the hole enlarged. Eventually on the next day the large chimney, formally used for the steam engine boiler, fell into the well, sealing the hole. (Photo Courtesy - Woodhall Spa Cottage Museum).

On the morning of the 21 September 1983, the secretary of the Spa Baths was called to the Well Room by the engineer, Mr. Bob Bloom. The water in the old spa water shaft was churning round and around and parts of the well sides were seen to collapse into the well. Within a few hours the hole had opened so that the outer wall gave way followed by partial collapse of the roof.

Within a day the foundations of the large chimney, formally used for the steam boilers, were undermined. It crashed down into the hole, striking the side of the water tower, and taking much of the remaining outer buildings with it. The enlargement of the hole having then stopped, the remains of the surrounding damaged buildings, plus several tons of limestone, was then bulldozed into the hole.

This incident marked the end of the Spa Bath shaft and since the North Lincolnshire Hospital Board had already decided to build a new treatment centre in Lincoln, the Spa Baths Trust that managed the Spa Baths was unable to continue in its former form. They still continue to provide grants towards medical services from the income from the sale of the Baths and the Alexandra Hospital.

Spa treatments began to go out of favour in the 1960s and by the 1980s there was declining interest from the National Health Service. It was generally considered that the application of radiant heat did little to promote permanent cures, though the treatment gave considerable relief for a short time which promoted considerable well being. It was generally considered that the drinking or application of the spa water was of little benefit.

Photo 13 - After the collapse, the rubble from the destroyed and damaged buildings were bulldozed down the hole, followed by 500 tonnes of limestone. (Photo courtesy Woodhall Spa Cottage Museum).

However some research in Bath suggested that immersion and drinking the spa water may have had some success in the 19th and early 20th Century for successfully treating some forms of gout. This was because, it was suggested, many of the forms of ailments described as gout in the 19th century were in fact cases of lead poisoning. Lead was commonly used for table glasses, lead pipes and various lead glazes uses in pottery increasingly throughout the industrial revolution until the 1950s. Much of this lead got into the diet producing chronic lead poisoning. Immersion and drinking water with a high specific gravity helped to purge the lead from the system, thus relieving the “gout”.

Spas and spa water is still actively used on the continent, particularly in Eastern Europe and it is an interesting fact that the Woodhall Spa Baths was better know in Germany in the 1970s than it was in Britain.

Photo 14 - Rear view of the Pump room from near the well head. (Photo from the Website Administrator's collection)

The Spa Baths Today

The Spa Baths were subsequently closed and went into private ownership. Unfortunately, the historic buildings to which Woodhall Spa owed its existence were an eyesore until 2022.

The good news is that a local building firm (GN Construction) purchased the site a few years earlier and set about refurbishing the building in 2020 to serve a variety of purposes. The first section reopened in November 2022 when 'Expressions Hair & Beauty' relocated to it. Now known as Re:New Hair and Beauty by Expressions.

Work to refurbish the Spa Baths began in 2020!

Photo 15 - Inside the Pump room looking towards the Main Entrance. (Photo from the Website Administrator's collection)

Media attention

www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-lincolnshire-29075897

Updated 31 Dec 22

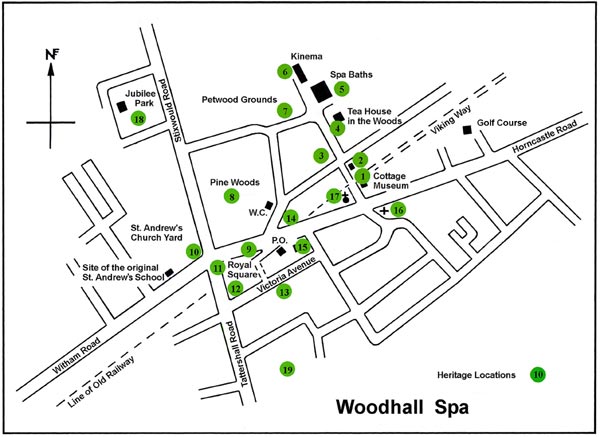

Heritage Trail locations

The trail can be started at any location, but we suggest you also visit the Cottage Museum to see the photographs taken by John Wield during the heyday of the Spa and items associated with this unique Victorian Spa town.

The Trail is just one of several projects in the hands of the Woodhall Spa Parish Council sponsored Heritage Committee. Click here if you are interested in the committee or their projects.

How well do you know Woodhall Spa?

See if you can identify the location of these architectural features and items of street furniture! Or find the Letterbox (coming soon).

Find out more about the Woodhall Spa Conservation Area